- Home

- Cycling Holidays

- Destinations

- Provence

Guide to Roman Provence

Provence is a fantastic region to visit for many reasons. The beautiful villages, the rolling vineyards, the great food and the superb climate are just a few. But it is also a region whose culture and charm has been influenced by thousands of years of history.

And one of the great things about Provence is that it is alive with reminders of past eras. Buildings like the Palais des Papes in Avignon or the hilltop castle of Gordes all help to tell the story of the region's history.

Most impressive and extensive of all, in our opinion, are the ancient monuments. And in this guide we will be introducing some of the best Roman ruins in Provence, and revealing a little about the stories behind them. These are monuments that we visit on our cycling holidays in Provence, and are all within a relatively small area.

Use the map and links below if you are interested in finding out more about a particular place. Or, for a more detailed history of Roman Provence, simply continue reading down the page!

Provence Before The Romans

The River Rhone near Avignon

From the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, Provence was mostly inhabited by Celtic tribes. Known as Gauls, they were groups who had migrated from Central Europe and inhabited most of modern day France, Belgium and Northern Italy, as well as areas of the Alps.

Many Gauls lived in small towns, known as oppida often located on hilltops and were split into hierarchical societies, with a small but powerful ruling aristocracy. In Provence, many were involved in farming, taking advantage of the fertile soils of the Rhone valley. But they were also warrior societies. The Gauls regularly attacked their neighbours, looking to plunder resources and capture slaves.

From around the 4th century BCE, one of these neighbours was Rome - at this time still a relatively small city state, but gradually expanding its territory in Italy. The Gauls famously sacked Rome in the year 390 BCE, and their fierce temperament made them greatly feared by the Romans.

But the Gauls of Southern France were not just some group of bandits, going round and stealing from other peoples. They were involved in trade networks and would exchange goods across the Mediterranean. Much of this was facilitated by the Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marseille) which had long vied with Carthage for dominance of the Western Mediterranean.

Massalia was also allied with Rome, and so directly or indirectly there was significant contact and exchange between the Gauls of Provence and the Romans; even as they continued to eye each warily. Gaul was still regarded by Rome as being the land of Barbarians, and they had neither the means nor the will to try to conquer it at this time.

Hannibal in the Alps - Pauwels Casteels

The situation changed in the 3rd century BCE. Rome had gradually become more of an expansionist power. Firstly they extended their territory into Southern Italy, and then they conquered some of the Gauls living in Northern Italy. This moved the Roman frontiers closer to Provence, although the formidable barrier of the Alps remained in between.

The big catalyst though were the actions of one of ancient history's most enduring figures: Hannibal Barca. In the year 218 BCE Hannibal led Carthage into war against Rome, following a long and bitter dispute over control of Spain. The war lasted nearly two decades, as Hannibal crossed the River Rhone, then the Alps and took the fight to Italy.

Rome eventually won the war and their main prize was that they ended up in control of much of Spain, including its entire Mediterranean coastline. From then on, it was almost inevitable that the Romans would look to conquer Southern France at some point, as they were in need of a land route between their Italian heartland, and their new rich provinces in Spain.

Initially, Rome reached an agreement with some of the Gauls living along France's southern coast, to allow them to pass through on their way to Spain. But it was a precarious arrangement due to the warrior nature of both sides. And so, by the 120s BCE, Rome made the decision to try to conquer the territory and ensure that it would remain pacified.

Orange

Orange Roman Theatre

A decisive moment in the history of the region occured in the year 121 BCE, at the Battle of Vindalium. The location of the battle was near to the town of Sorgues, in the vineyards just to the south of Orange. The Romans emerged victorious over some of the Gauls in the area, and followed it up with several other victories over the next few years.

The result was that the region had become a Roman province. Its official name was Transalpine Gaul (literally - Gaul on the other side of the Alps). But, more colloquially, it was known as Provincia Nostra ('Our Province'). Which, if you hadn't guessed already, is from where we get the name 'Provence'.

At this point, Rome still saw Provence mostly as simply a gateway to their Spanish provinces. Their main action was to construct the Via Domitia - a road running through the region - and to build a couple of safe towns along the route. Orange remained a small Gaulish settlement, known as Arausio, and wouldn't be re-founded as a Roman city until 35 BCE. And the great theatre which dominates the town today, wouldn't be built until the early 1st century CE.

Triumphal Arch - Orange

That is not to say that the early years of Roman Provence were uneventful. In the north of Orange today, a large triumphal arch stands in the middle of the main road out of the city. It's decorated with glorious scenes of Roman victories over Germanic tribes, and was a propaganda piece installed by the emperor Tiberius in the early 1st century CE, to promote victories in Germany.

And Orange was not chosen by chance as the location for the arch. One hundred and thirty years before its construction, in the year 105 BCE, Orange was the scene of a battle that nearly saw them lose control of Provence.

The opponents were Germanic tribes who had migrated from modern Denmark in search of more fertile lands and a less hostile environment. Rome had refused their requests to settle peacefully in Provence which led to an encounter near to Orange (or Arausio as it was then known).

Rome suffered a horrendous defeat, and there was a genuine fear that they might not only lose Provence, but that the Germanic tribes might march on Rome itself! The Battle of Arausio was so bloody, that the ancient historian Plutarch claims it was responsible for the productivity of the surrounding vineyards. He claimed that it was only thanks to the amount of blood spilled on the fields that they became so fertile for years to come. Which isn't the most appealing thing to think about when you're tucking to a glass of Châteauneuf du Pape!

In any case, in a state of panic, Rome turned to their most trusted general, Gaius Marius. He advanced his Roman legions into Provence and was able to save the day, defeating the Germanic tribes at a battle near to Aix-en-Provence.

This was a major turning point. Provence remained a fairly secure possession of Rome for the following few decades, encouraging great migration and investment in the region. Although there were still a few more hurdles to overcome before conditions were right to build great monuments like those still standing in Orange.

Glanum

Mausoleum & Victory Arch

Glanum is the most complete ancient archaeological complex in France, and it also reveals a fascinating history. The extensive ruins that you see today highlight what Provence was like in the first few decades after the Roman conquest.

Throughout the site today you can see evidence of the gradual change in Gaulish society. Glanum was originally a Gaulish oppidum, and the thick walls and defensive fortifications remain standing in the town - a relic of the warrior society. But you can also see that Glanum had already become somewhat civilized before the arrival of the Romans.

One of the best preserved buildings is a Greek style house, and there is also evidence of the Greek influenced Bouleuterion (a kind of open air city council). The Gauls of Glanum were not some Barbarian savages when they were conquered by Rome, they had been heavily influenced by the Greeks of Massalia (Marseille) for centuries, and had a relatively advanced political structure.

This process of civilization - in particular a focus on trade and diplomatic relations rather than raiding - continued in Provence throughout the early 1st century BCE. The city leaders saw the advantages of allying with Rome rather than opposing them. They were able to import prestige goods and improve their wealth and status, without the need for potentially dangerous raids.

It wasn't always a smooth process, but the Gauls of a town like Glanum were, over a long period of time, becoming a bit less Celtic and a bit more of a typical Mediterranean culture.

Greek Style House - Glanum

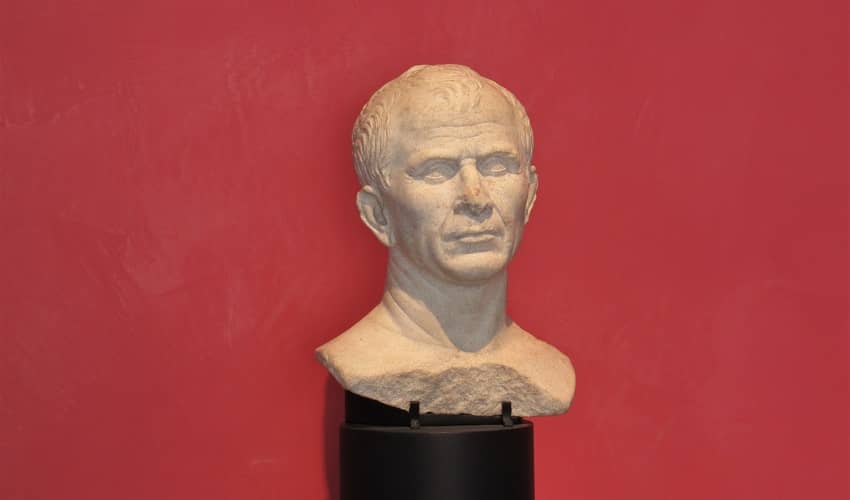

This was the situation when a new Roman governor showed up in Provence in the year 58 BCE. The governor was Julius Caesar - perhaps the most famous (or infamous) man in all of history. Caesar was in huge financial debt when he arrived in Gaul and he also was craving glory to enhance his political career. The solution to both of these issues was to conquer more of Gaul.

Over the best part of a decade, Caesar systematically conquered all of modern France and Belgium on behalf of Rome, and even made forays into Britain and Germany. In his accounts of the conquest, Caesar always justified the expansion as being necessary to keep peace on the borders of Provence. But it's easy to be cynical of this, given how much he improved both his reputation and his bank balance in the process.

It was not all plain sailing, there were moments when Rome was nearly defeated and thrown out of all Gaul. Most notably when Vercingetorix led a revolt in the year 52 BCE involving almost all Gaulish tribes. But Caesar's legions emerged victorious, thanks, in no small part, to alliances he made with influential Gaulish elites.

At the entrance to Glanum today stands a victory arch and a Mausoleum known as Les Antiques. The Mausoleum dates from around 40 BCE and commemorates an aristocratic Gaulish family from the town. They were some of the many Gaulish nobility that supported Caesar against their fellow Gauls, having become convinced of the advantages of being under Roman control.

These Gauls had been rewarded by being made into official Roman citizens by Julius Caesar. He gave them his name, and from then on, this Gallo-Romano family were known as the Julii.

Temple of Augustus & Forum - Glanum

Conquering all of Gaul was not quite the last action that Caesar would take in Provence (we will see more below). But it was the one with the most profound impact for the region. It meant that Provence was no longer on the edge of the Roman world; in fact, it was now a secure possession, mostly surrounded by other Roman provinces.

It was clear that Rome was now going to be in the region for the long haul. When Caesar's adopted son - Augustus - became Rome's first emperor in the late 1st century BCE, he encouraged building projects and investment in the region, as well as the expansion of existing trade networks. Again, this can be seen in Glanum. The Roman forum was built around this time, as well as a basilica, curia (senate house), Roman temples and various other facilities.

The secure nature of the borders had enabled this and, with the warrior nature of the Gauls decline sharply, they continued to become ever more immersed in the Mediterranean world.

Arles

Arles Amphitheatre

Julius Caesar would still leave his mark on the region. Specifically, in the city of Arles, which would become one of the most important and prosperous in the western half of the Roman Empire.

In the process of conquering Gaul, Caesar had ended up on the wrong side of many important senators in Rome. They were annoyed that he was monopolizing all of the glory and feared that he had become too powerful. They encouraged Rome's other finest general and conqueror - Pompey the Great - to oppose Caesar and knock him down a peg or two.

The senators outmanoeuvred Caesar politically and backed him into a corner, where it looked as though he would be forced to give up much of his political power. However, Caesar responded with the unthinkable. He crossed the Rubicon River that was the border between Gaul and Rome; and he marched his legions on the capital, igniting a civil war in the process.

Caesar marched into Rome unopposed, as Pompey and the other senators had already fled. And his next act of the civil war was to head off to Spain, with the intention to defeat Pompey's legions which were stationed there.

Bust possibly of Julius Caesar - Arles

On his way to Spain, Caesar had planned to stop off in Marseille (Massalia) to break up the journey and to resupply. But, when he arrived, he found the gates of the city firmly shut, and it soon became clear that they were backing Pompey.

Fortunately for Caesar, the neighbouring city of Arles offered their assistance to him. At the time, in 48 BCE, Arles was a medium sized Gaulish settlement. It had steadily become Romanized over the previous decades and was quite prosperous thanks to its control of trade along the River Rhone, but it was still dwarfed in importance by the great Greek colony of Marseille.

After dealing with Pompey's legions in Spain, Caesar returned to Marseille and the city was taken after a long siege. He punished Marseille by confiscating some of their territory, as well as taking much of their gold and other valuable possessions. Much of this was transferred to Arles, as a reward for their help, giving the city a huge economic boost in the process.

Roman Theatre - Arles

Three years later, Caesar had won the civil war. He had defeated Pompey in Greece and had overcome the rest of the senators who had fought against him. He was now the unopposed dictator of Rome.

He returned to Arles in 45 BCE and formally refounded it as a new Roman colony (known as Arelate). To make it a worthy Roman city, he furnished it with an impressive forum area, including a basilica and temples. The aim was to further erode the importance of Marseille, and to turn Arles into the most important trading center in the region.

Over the following century, Arles continued to grow. Its location, at the mouth of the River Rhone, was ideal for controlling the extensive trade flowing from Western Mediterranean to large inland cities like Lugdunum (Lyon) and Augusta Treverorum (Trier).

Goods like olive oil, wheat and pottery would all make their way up the Rhone in vast quantities. Huge warehouses in Arles were used by merchants to store goods. While the city's port and basilica were hives of activity as merchants from across the empire would travel there to negotiate contracts or do other business.

Baths of Constantine - Arles

Huge wealth flowed into the city; and the powerful local elites spent much of it on building extravagant monuments. The theater and amphitheatre that still stand today, as does a small section of the circus.

Backing Caesar had proved to be an incredible stroke of fortune, as Arles would maintain this privileged status throughout the Roman Empire. In the 4th century CE, the Emperor Constantine built a fine new bath complex close to the River Rhone, which was part of his imperial palace in Arles.

Arles, and Provence in general, had become an integral part of the Roman empire.

Nimes

Tour Magne - Nimes

Similarly to Arles, Nimes was also founded as a Roman colony in the late 1st century BCE. Known as Nemausus, it was at a strategically important location along the Via Domitia road, running across southern France, and it was populated with Julius Caesar's veteran soldiers.

By the time it was founded, though, Caesar himself had already been dead for the over fifteen years. His assassination by senators in Rome had led to another long and bloody civil war which raged across the Mediterranean world. Caesar's adopted son - Augustus (also known as Octavian at that time) eventually emerged victorious, after defeating Marc Antony and Cleopatra in Greece.

Shortly afterwards, Augustus was effectively appointed by the senate as Rome's first emperor, ending nearly five hundred years of Republican rule. During his long reign, he began to shape the empire in a way which would endure for centuries.

Statue of Augustus - Nimes

Colony foundation was a key part of this. Augustus needed new towns where he could settle his soldiers as part of their retirement package, but he also wanted to stamp Roman culture and imagery in provinces throughout the empire.

He personally sponsored a large number of building projects in Nimes, including the 6km (four mile) long city walls, of which the Tour Magne still remains. Augustus was also a great self-publicist and so named one of the gates after himself - the 'Porta Augusta' - and he encouraged the building of temples where his personality could be worshipped by local subjects.

He also furnished the city with an attractive forum area and other temples, where more traditional Roman gods could be worshipped. None of this was unique to Nimes - the process was being repeated throughout the Empire - which by now encircled the entire Mediterranean.

It was a key step in the culture within the Roman world becoming more homogenized. Colonies like Nimes were not just inhabited by Roman citizens, but also by local peoples, who would then be ever more exposed to the Roman economy and Roman society.

Nimes Amphitheatre

Throughout the 1st century, the Roman empire continued to become ever more interconnected, both economically and culturally. Local elites in a place like Nimes prospered more than most. They controlled most of the new industries and many were able to accumulate large estates. They would use their money to gain political influence, with the aim of ultimately being admitted into the Roman senate. One emperor - Antoninus Pius - could even trace part of his family history back to Nimes.

As part of their effort to win local elections and, ultimately to gain the favour of the emperor, local elites began to sponsor their own great building projects. The stunning amphitheatre at Nimes was one such example. One of the largest in the entire empire, it was paid for by local elites in the year 70 CE as a way to win the favour of the people of the city.

The amphitheatre hosted gladiator combats and animal fights, events which were also paid for by prominent local politicians, as they looked to win the favour of their electorate. Some historians have described it as a kind of social contract; whereby certain individuals were allowed to accumulate huge power and wealth, but were expected to give something back in return.

The Roman poet Juvenil was a little more cynical. He disparagingly labelled it bread and circuses, claiming that the whole thing was just superficial appeasement and a distraction to the genuine poverty and suffering of the poorer members of society. In any case, the elites of Nimes certainly didn't skimp on the quality of the construction. The arena still stands nearly 2,000 years later, and even continues to host bloodsports today, in the form of bullfights.

Maison Carrée

The reforms and colony creations by Augustus had set the Roman Empire on a successful course, but there was still one major issue. Who would replace him? And this is an issue that is laid bare in another of Nimes' most impressive monuments - the Maison Carrée.

The Maison Carrée is a stunning building that was situated in the heart of the ancient forum. It is beautifully decorated with a classical facade that is supported by six impressive Corinthian columns. The building was a temple and was dedicated to two of the grandchildren of Augsutus: Lucius and Gaius Caesar. They had both died on military campaigns at a young age and a devastated Augustus deified them and encouraged worship of them in the temple.

The two young men had been earmarked as potential successors as emperor, and their untimely deaths caused problems for Augustus. He was forced to scramble around for a successor, and eventually he reluctantly settled on his step-son Tiberius. But the lack of clarity in his choice ended up setting a bad precedent for decades to come.

The imperial household became a place of great intrigue as men and women manouevred behind the scenes to try to set their relatives or favoured candidate up as the next emperor. And it was almost as common to get a 'bad' emperor like Caligula or Nero, as a 'good' one like Trajan or Antoninus Pius.

Ultimately though, the structures and institutions that Augsutus had put in place were incredibly strong and well founded. To the extent that, for a place like Nimes, it didn't really matter who the emperor was. He and his family would be worshipped in temples like the Maison Carrée as part of Roman religious rituals, but business and life would carry on more or less as normal, regardless of any intrigue going on in Rome.

Pont-du-Gard

The 300m (1,000ft) wide bridge crosses the Gard river and was part of an incredible 50km (31 mile) long aqueduct that carried water into Nimes. It was constructed in the 1st century CE by the Gallo-Roman elite to improve both the prestige and the living conditions of their city.

The aqueduct brought running water into the homes of influential citizens and also fed the city baths and fountains. It was a standard of infrastructure that was unheard of in Provence before the arrival of the Romans; and the aqueduct helped to improve sanitary conditions in the increasingly densely populated city.

The bridge was the embodiment of the power of Rome and the local elites; who were stamping their authority on the physical landscape. The aqueduct was a stunning display of engineering, and would be even by today's standards. Over its 50km length, the aqueduct descended just 12.6m (41ft) - an almost imperceptibly small gradient of 1 in 18,241. And Roman engineers had managed to make this consistent with expert precision. The Pont du Gard aqueduct descends just 2.5cm (1 inch), which was enough to keep the water flowing into Nimes at the desirable rate.

The aqueduct was also constructed largely without the use of mortar. The large stones were precisely cut and winched into position, where they formed columns and arches that were held in position by the pressure they exerted. And they remain in position today, some 2,000 years later.

Such imposing displays of technology and power, particularly when used to benefit local populations, were a great way to limit potential rebellions against the ruling elite.

Vaison-la-Romaine

Not having to worry about being attacked or raided had a huge impact on the lives of people in Provence, they could make long term plans and decisions in the knowledge that Roman law offered them some kind of assurances and stability. Trade was encouraged, and it was now possible for a farmer living in Provence to focus exclusively on one product (for example grapes or olives), knowing that he would easily be able to go into the city's macellum (market) and find a buyer. Being a subsistence farmer was no longer the only option available for many people.

A town like Vaison-la-Romaine was a place that greatly benefitted from the Pax Romana. It became very wealthy thanks to the fertile lands in all directions, and the access to the entire Mediterranean trading circuits via the River Rhone. Many town houses in Vaison have been found with high quality mosaics and imported pottery. Such long term prosperity would have been almost unthinkable two centuries earlier, with Gaulish warriors regularly rampaging through the countryside, destroying crops and plundering the valuables.

Like in Nimes, the wealthy members of society spent money on the town, furnishing it with buildings such as the great theatre and thermal baths which remain today.

Roman Bridge - Vaison

This period of great peace and prosperity lasted until the end of the 2nd century. Political instability then began to boil over, several pandemics ravaged the countryside and warriors on the fringes of the empire became more powerful.

From the 3rd century CE, many of the smaller towns in Provence, like Vaison, began to decline. Life had become a bit more insecure, with the destruction of civil war and raids by warriors becoming a more common occurance. The wealthy citizens became less involved in city life and increasingly retreated to large villa estates, which were almost completely self sufficient and easier to defend.

They no longer had any need to furnish a place like Vaison with grand new buildings, and the city fell into something of a decline. The Pax Romana and the great period of prosperity in Provence had come to an end.

The End of Roman Provence

Atilla the Hun - Raphael

The fortunes of Roman Provence didn't decline in a linear fashion. There were some very prosperous periods throughout the 3rd and 4th centuries. But as the borders of the empire became less secure and as the Roman world gradually shrank, trading opportunities became more limited, and the Gallo-Roman elites in southern France became more insular.

The 5th century saw large numbers of so-called 'Barbarian' groups moving into Provence, either as raiders or permanent migrants. The Vandals sacked some of the great cities of the region, while the Visigoths laid siege to Arles, before finally deciding to settle around Toulouse.

Meanwhile, Atilla the Hun was causing all kinds of destruction in Northern Gaul, as the Roman state had lost its firm grip on power.

The Coronation of Charlemagne - Raphael

Unlike in Northern Gaul or Britain though, the Roman empire, in terms of its institutions and structures, never did really collapse in Provence. Cities were never completely abandoned, and a place like Arles continued to be very active in Mediterranean trade routes. Wealthy aristocrats continued to wield significant political power across large areas, and crops such as wine and olives continued to be farmed on an industrial scale. Latin also continued to be spoken.

But everything became a bit smaller and less grand in scale. Local markets had fewer things for sale, there was not enough money or security for building projects, and the threat of raids from Barbarian tribes was ever present. Theatres and Amphitheatres were no longer used as entertainment venues, but rather as fortified buildings were people could shelter from attack.

With the decline of the centralized Roman state, local bishops and other elites took on an even more important role, and would make deals with warlords to keep their region prosperous. It was a much more unstable existence, but life certainly went on in Provence.

This period of transition lasted for a few centuries until the map of Europe took on a different shape once more. The emergence of Charlemagne - king of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor - opened up a new chapter in the history of the region. The Christians from Northern Europe vied with the Muslims of Al-Andalus for control of Provence. And this new era was one where regions were increasingly defined by religion and religious culture. But that is a topic for another day.

Amazingly, the buildings and towns that we've looked at are just some of the fantastic Roman sites in Provence. There are many more along the southern coast from Marseille to La Turbie, and, of course, beyond into Italy.

We visit most of the above monuments on our cycling holidays in Provence. So if you would like to see them first hand and learn more about the incredible history, come and join us!

Our cycling holidays near to Provence

France

France